Oral History Education: Documenting the Important Stories of Ordinary People

Oral history projects provide primary source materials that aid us in our understanding of the past. From oral history interviews we gain what is often missing from textbooks perspective. Oral history projects in the classroom give students a personal perspective, helping them connect to and make more meaning from the past.

There are terrific resources on teaching with oral history that are available online. Some of the resources that have been useful to the Civil Rights and Apartheid projects. This website was developed so that history teachers worldwide could download the curriculum for free and order the documentary. At some point the site's domain registration expired and the site disappeared from the web. The new owner of this site felt that the information provided should not be lost and used content from the original site's 2008-2012 archived pages.

My daughter's 11 grade social studies teacher utilized some of the lessons plans from OralHistoryEducation.com. I vividly remember the oral history projects class assignment that was assigned my daughter. She decided to interview her 95 year old grandmother who had immigrated to the US from South Africa. She had lived through the Boer War, the ascendance of the Afrikaner National Party in the 1940's whose strategists invented apartheid as a means to cement their control over the economic and social system and in the 1960's the implementation of the "Grand Apartheid" plan that emphasized territorial separation and police repression. My daughter was entranced with her grandmother recalling the enactment of apartheid laws in 1948 where racial discrimination was institutionalized and then in 1950 when the Population Registration Act was passed that required that all South Africans be racially classified into one of three categories: white, black (African), or colored (of mixed decent). We received excellent help in finding more information online from the search experts at TNG/Earthling. I often free lance for them and called in a favor and we are very glad I did. We received a ton of very valuable historic info on all of the most significant events surrounding that time. I edited it down to not be an overwhelming read, but my daughter wanted to go through everything! After a very thorough research job, she finally finished her oral history project and turned in both a written paper and a video she had made of all the interviews she did with her grandmother. Now having told my story...please enjoy and be inspired by this site.

Background History About this Site

In 2008 a 10-minute trailer of Journeys of Reconciliation was screened at a fundraising event on March 9th. The event generated much enthusiasm and support, and we continued to reach out to our friends, corporate sponsors and foundations to raise the required funds to complete this project.

The final four days of filming were completed in South Africa in June, 2008. The addition of historical footage and post-production editing was scheduled for June – August, and the documentary was completed by September 2008.

Beginning in September, a team of educators from South Africa, Stanford, San Francisco State University, and USF started work on curriculum development for lesson plans to accompany this documentary in the classroom. The curriculum met the California Content Standards for Grades 10 and 11 Social Studies, and educators were eager to bring Journeys of Reconciliation into their classrooms. We worked with educators from the San Francisco Bay Area and Johannesburg to pilot this social justice project in their classrooms.

++++

Students can bring history to life by documenting the important stories of ordinary people. This is a process that helps students to think like historians as they become active participants in history rather than just consumers of it.

A short, ten minute documentary was made to demonstrate the use of oral history projects in the classroom. As seen in the short film, oral history projects spark an intergenerational dialogue, crossing the barriers of age, culture and race. This process is one of discovery for both the student and the person they interview.

Sometimes, oral histories on a topic will cause us to reevaluate what we know. However, it is important to understand that oral histories are a part of a bigger story. Noted historian Elizabeth Tonkin explains that oral history helps us to “understand how history as lived is connected to history as recorded.” Students can make this important connection through thoughtful lesson plans in the classroom.

+++

Storycatcher At Large

Q & A With Storycatcher At Large

February 24th, 2011

A “sister” topic to oral history interviewing is memoir writing. As part of a dialogue with Denis Ledoux, a memoir writing teacher, I answered 10 questions about oral history interviewing.

1) What process do you go through—and by extension what methods would you recommend to a lifewriter to prepare yourself and the interviewee for an interview?

To start, be a truly good, authentic listener from the very beginning of your project.

There are two kinds of oral history interviews that I prepare for prior to recording an interview: 1) Life stories, in which I work with individuals who want to record their life experiences, and 2) Subject based projects where community groups or museums hire me to focus on a particular event or period in history.

To prepare myself for these interviews I communicate with the interviewee to develop a healthy rapport, and to build trust with him/her. I do this through whatever mode of communication works best for that person – emails, in-person visits, telephone calls, and letters. I take notes about the topics, interests, events, and issues that come up, and then do as much research as possible to develop a solid understanding of them. My research includes online searches with credible sources, and always involves several trips to my local library to access both its online and on-the-shelf resources.

For example, I am currently preparing for interviews with Vietnam Veterans who returned from a painful war to a painful homecoming. These veterans courageously rolled up their sleeves and got to work helping other veterans heal and move forward to become part of their communities. Nearly 40 years ago, they formed what is today a national model for veterans programs, Vietnam Veterans of California. Preparing for my interviews with a team of founding veterans seemed overwhelming at first, until I started listening closely to their perspectives during my pre-interviews on the phone, and in my email correspondence with them. By this time I had read nearly two dozen books and novels that focused on many different perspectives of the war – the stories of combat soldiers, of anti-war activists, military history and strategy, and contemporary stories of soldiers from Iran and Afghanistan. The key, I’ve found is being a good listener from the start, because that is what they need. Being a sincere, active listener is what will drive the narrator to tell his/her story.

2) How do you decide what questions to ask and what tips can you offer on how one might craft these questions?

The general “rule of thumb” for crafting interview questions is to make them open-ended, rather than closed. A good open-ended question inspires an answer that is descriptive of a thing, place or event. For example, “Could you describe the home town you grew up in?” compared to a closed question, “Where did you grow up?” The natural flow of an interview will have both kinds of questions, however to facilitate storytelling that is meaningful, it is the open-ended questions that will make the difference.

I don’t take a long list of questions with me to an interview, because that can be intimidating to an interviewee. I have found over the years that each interviewee has a story that will unfold naturally. So, as I pay close attention to the early, informal conversations with an interviewee, and as I conduct my research, I outline the topics and possible questions that will link to their experiences.

Sometimes a question becomes clear to me for a group project, especially a question that provides contrasting perspectives on an event or period of time. For example, “How did that ‘event/happening’ affect you at the time?” And then a follow-up question “How does that ‘event/happening’ impact you today as you look back on it?”

Follow-up questions are really the key to a good oral history interview. Useful follow-up questions require one to be a deep and active listener. These questions draw out the details of a story. Follow-up questions help us to overcome the assumptions that most people make, which are that the details will be inferred, or are already known. The intention is to help or facilitate the storytelling process by asking a follow-up question that fosters a story and encourages the storyteller – questions that show you are really listening, and that demonstrate that his/her experience is valuable and important. The intention, by contrast, is not to “dig” for more information, or to contradict, or challenge the interviewee. Oral historians are not journalists. We do not have an agenda, so it is important to know the intention behind our questions. They are designed to help and to encourage the interviewee.

I have posted tips on interviewing and examples of questions on my website and in a SlideShare presentation for teachers to use for classroom projects (see below). Another good resource for ideas and questions is at Story Corps website: http://storycorps.org/record-your-story/question-generator/

Educational SlideShare Presentation

Oral History Education ~ Bringing History to Life

View more presentations from My Storycatcher

3) What resources and tools are useful to someone doing oral history?

First, the Oral History Association is a wonderful organization and their conferences and publications are excellent. The OHA website also contains very useful resources on best practices in the field: www.oralhistory.org. Second, local libraries and museums in the region you are working in are very valuable resources. Many libraries and local history museums manage archives of local newspapers, and you can access articles by topic that give context to a period of time or to a subject. Make an appointment with the research librarian to get started, and plan the time to do this research before the interview.

For teachers, I highly recommend Glenn Whitman’s book, “Dialogue with the Past: Engaging Students and Meeting Standards Through Oral History.” Whitman provides a step-by-step guide for teachers that is thoughtful and wise.

Using the best recording equipment you can afford will make a tremendous difference in the sound quality of your interviews. I use a terrific digital audio recorder, the Marantz PMD670, with a high quality external microphone to get broadcast quality interviews. These types of recorders are becoming more affordable, and are very durable and easy to use. I’ve used my recorder in the field, literally, with Northern California farmers who represent the 3rd and 4th generation of family run farms. So, they are portable and easy to use. When using a microphone outdoors, be sure to use a windsock, and carry back-up batteries. Most of my interviews happen around the kitchen or living room table, but getting out into the community with your recorder can add important depth to a story.

Regardless of your budget, use what you have available and get to know how to use your equipment – become an expert on all of its functions and capabilities. The manual that came with my recorder is very well read – with notes, highlights, and coffee stains.

If you are using video equipment, practice videotaping so that you have established good skills. There are good tips out there on You Tube and many books on how to position someone on camera, set-up lighting, etc. Be sure to use a tripod, and if you don’t have an external microphone (most home video cameras do not) then place the video camera relatively close to the interviewee so that the internal microphone can capture decent audio. Community colleges offer very good courses on digital video, and are inexpensive. I took two courses at my local junior college, for about $90 each.

You will then need to capture (or upload) the audio/video to a computer with editing software (iMovie, Final Cut Pro, Avid, etc.) AND BACK IT UP onto an external hard drive. I do this the same day, or the very next morning of an interview.

Creating a transcript of the interview is the next step. It is difficult work, and harder than it looks. I found an affordable service in my area after asking for bids from several vendors. Go to the OHA website to learn what to do, and what NOT to do when transcribing an interview.

If you are creating an oral history archive for a museum or library I recommend following the best practices guide on the OHA website, and consulting with the Collections Manager or Archivist at your local history museum.

4) Are there any special techniques you would recommend when interviewing a young individual?

I think it is important to be aware of the myths and assumptions we hold about youth, and for that matter, any age different from our own. We need to check our assumptions and see the interviewee as a unique individual with an important story, regardless of age. It is also important to pay attention to the interviewee’s use of language and vocabulary because every generation has their own way of saying things. It is important to respect this and to incorporate their vocabulary into our own during the interview. An interviewee’s choice of words is an important aspect to the record of history being created.

Involving a young interviewee and engaging him/her will also be key to a meaningful interview. Find out what he/she cares about; what activities, music and interests he/she enjoys. Participating in an oral history interview is usually voluntary, so the intention behind the interview is important – find out what it is.

5) How do you deal with the issues of false memory or doctored responses, and how would you suggest an oral historian might go about detecting these?

This is an important question. We want to get away from “doctored” responses and record authentic, genuine stories of a how history was lived and experienced.

Memory is an interesting, and complicated process that relies on a variety of factors. Memories are created in different parts of the brain, depending on how the information is coming in: verbal/auditory, visual, sensory/touch, smell/taste, and emotional/feeling. As the sensory data is being processed, our brains store long-term memory in a variety of locations. We tend to remember things more vividly when there is a combination of strong sensory inputs, especially when combined with a strong feeling.

As far as dealing with false memory, that is something we will not have much control over. What we are recording during an oral history interview is an individual’s translation of past events. Therefore, some of the meaning will be lost in translation.

What we are valuing here is the narrator’s point of view, so essentially we are capturing how history is remembered as well as how it was experienced. Some will be credible, honest and valuable narrators, and some will not. Hopefully, we can discover this during our pre-interview conversations so that we can be aware of false memory issues or what Allesandro Portelli calls “misremembering.”

This being said, however, oral history interviewing is an intimate process that requires a level of trust. This means we are not there to contradict the narrator, we are there to aid him/her in their recollection of past events. If the narrator is confusing one event with another event, we need to respectfully help him/her clarify for the record. For example, if a narrator is confusing two different occasions, you could ask a clarifying question like, “Do you recall if the ‘event’ was prior to this occasion or following it?”

Almost everyone “doctors” the past in some form or another, however if it is clear to you that this is intentional, and therefore the interview is not going to be valuable, you may want to consider some options. You could either give the person more time talking with you “off the record” to get more comfortable and build trust, or schedule a series of shorter interviews. If you are getting a “doctored” or “canned” response during the interview ask a different question, something that hasn’t been asked before and that they were not expecting. This can make for a much more interesting, authentic interview.

6) What methods could an oral historian use to challenge or validate the recollections of interviewees?

As I explained above, we don’t want to put ourselves in the position of challenging a narrator, however we do want to help facilitate good memory recall, and a healthy dialogue that evokes good storytelling. Storytelling is a very natural process that families and communities have used to pass on knowledge for many centuries. Validating narrators as they share their memories is important because it takes courage on their part to participate in an interview, and because this is a very human process.

There are many ways to assist a narrator with their memory recall:

a. Photo Elicitation: Work with the narrator on a photo collection that will help them to prepare for their interview. This takes time, but is very effective. As I work with narrators, I scan and preserve the most important photos for them and give them a CD for their own personal collection. As we talk about the photos, I make a log with dates, and descriptions of the people, places and events they relate to. I can then use the photos during an interview to help the narrator both recall his/her memories and organize his/her thoughts.

b. Objects: Narrator often refer to objects in their home that have significant meaning, like a childhood cup, military medals, linens, or a restored car from their youth. These objects are a wonderful source of memories, and can be photographed as part of the record, or videotaped. During the interview(s) you can ask the narrator to show the object, describe it, and talk about the memories associated with it. Why is it important to him/her? How was it used? What memory stands out the most about this object? What does it represent?

c. Socializing: If it is a community based project, getting people together with a shared experience, such as the founders of a neighborhood organization, will help them reconnect to that time in their lives. A relaxed, social setting with good food is all that is needed. I have seen a collective time-line, enlarged and posted on the wall along with news articles, art, photos and other memorabilia be very effective at these kinds of gatherings.

7) Do you analyze the way in which an interviewee’s mind wanders or how they answer questions?

Yes, I do analyze this so that I can better word my questions, and structure the interview. Each narrator has their own style of communicating and putting memories to words. Connecting with each narrator’s style of communicating is important. If a narrator is prone to wandering, that tells me I need to help with questions that focus the story. If the narrator is a natural storyteller, and is able to feely respond to my questions, then my job is to stay out of the way, pay attention and ask good follow-up questions (see question No. 2 above).

8. How would you recommend someone doing oral history should handle subjects which are painful to the interviewee?

Most interviewees will have experiences that are painful, or emotional as they remember them. It is very natural for us to have feelings about the past. Sometimes, this process can help us reconcile our feelings in the present with what happened in the past. We often treat the past as either something to brush under the rug, or present it in a euphemistic way. The truth is, the past is often messy and disorganized, as well as painful. During pre-interviews, I ask my interviewees if there are any subjects they do not want to talk about, as well as what stories they will be sharing.

If a narrator is going into painful territory, pay attention to facial cues and body language, which will tell you whether to pause for a moment or take a break. Give them the space needed to feel, and to process, and offer empathy when appropriate. The narrator is in charge of his/her story, not the interviewer. Let your interviewees know this – that they have the ability to stop, pause, and begin when they wish. We are not therapists, however if we are sensitive and thoughtful, a narrator can develop confidence and even a sense of closure after sharing a difficult memory.

For military veterans or others who have experienced severely painful events, it is important to gain a good understanding of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) and to seek professional guidance. I have been mentored by a few experts who have experience dealing with PTSD. They have helped me to develop an approach when someone is suffering from PTSD. I caution anyone who might be dealing with this issue not to project too much onto the narrator. The narrator is participating because they want to – for, oral histories are always voluntary. Again, as in each case, the interviewee needs to know that he/she is in charge, and can stop or pause whenever needed. However, if during an interview, the narrator appears depressed, is expressing negative thoughts and not able to return to the present, be sensitive and offer another time to meet. In addition, after someone has shared a painful memory, ask a question that reconnects him/her to positive things in the present.

Being a sincere, caring listener is usually all that we need to be, however it is good to be aware of the impact the interview is having on a narrator, and respond with sensitivity.

9) Have there been any interviews which have shaped the way you perceive the world or the way you go about the oral history craft?

There have been many such interviews, but one that comes to mind immediately is an interview for an oral history project about the social justice movement against Apartheid in South Africa. The interview was conducted by a white student with a man who grew up in SOWETO during the student marches in the 1970s. SOWETO is a black township that was formed when the Apartheid laws designated the area for blacks only. Today, there are middle class residents rising out of its painful past, however the many poor residents living there, numbering over a million, are a daily reminder of the history of racism.

I was the oral historian in charge of training the students in this project, and preparing the narrators for their interviews. The student was well prepared, and did an excellent job asking about childhood in a racially biased society. The narrator, John Biyase, works in the field of race relations and reconciliation today, and was very willing to share his story of overcoming the oppression of Apartheid. At the end, the student asked what role forgiveness played in the country’s efforts to reconcile. Mr. Biyase responded by saying that forgiveness is what set him free. It was a profound moment, and he still remains an inspiring figure for me. An excerpt from his interview can be seen on my educational website, www.oralhistoryeducation.com.

10) How is oral history used by families–and on a larger scale–by libraries, museums, or other academic institution today?

As Charles Hardy, III has stated, “At heart we are all storytellers and the stories we tell have consequences in how we act in the world.” For families, the process of creating an oral history record can be exciting and heartwarming as family members are given a role to pass on knowledge and experience in a very natural way. Storytelling was the primary method of passing on knowledge and experience prior to the written word becoming the focus of record keeping. Additionally, as we age we begin to reflect with more perspective, and we begin to question how our life mattered to others. The process of oral history inspires a meaningful generational exchange and gives us the opportunity to reflect with purpose.

On a larger scale, libraries, museums and academic institutions can sponsor oral history projects that are community building and educational. Often, they work together to do this. An example of a large library project is the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress. This project has inspired community groups, colleges and schools to record the oral histories of veterans. Another result of the work at the LOC is free, educational materials that support such projects on their website: http://www.loc.gov/vets/.

Museums play an important role interpreting oral histories for the public through exhibitions that link artifacts, interviews and storytelling. An excellent example, out of many that American museums have produced, is at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle, Washington, where oral histories of Asian Americans have inspired exhibits and educational programs. Programs like this bring members of the community together, raise awareness of a shared past, and get people actively involved in history.

The final example serves as a university project that is truly a model: The Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Their oral history recordings and archival material provide a rich and diverse perspective on the civil rights movement in the U.S. Their website is: http://www.sohp.org/

+++

Oral History Stories

+++

Civil Rights Stories

Prior to the changes begun by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, “Whites Only” signs were commonly placed in restaurants, theaters, buses, trains, and other public accommodations throughout the United States. “Whites Only” was not just a sign to designate seating according to race, it was a sign that represented a sadly long history of discrimination against non-whites. Racial discrimination permeated the power structure of local, state and federal government and defined the nation’s culture on many levels.

Despite the pain and injustice experienced by many, stories from the movement demonstrate the courage of individuals of all races in the face of adversity and the resilience of communities striving for a more complete democracy. Although this history seems to be more and more in the distant past, the need for racial-healing today has been pointed out by leaders from a variety of organizations.

Students of the Civil Rights Movement have the opportunity today to develop more than knowledge, they have the opportunity to develop respect for the sacrifices of past generations and compassion for those who are different from themselves. Developing a better understanding of this history in the classroom can give students a better foundation for the decisions they will be faced with in the course of their generation’s social justice challenges.

While the battle for civil rights was largely fought in the courts and legislatures of the country, activists at the “grass roots” level were developing nonviolent strategies for social change. The “sit-in” movement began in the South in February 1960 after four black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat at a whites-only lunch counter to protest racial segregation in restaurants. Freedom Rides were staged by black and white students protesting segregation on interstate buses. Peaceful marches were organized, including the 1963 March on Washington – the largest peaceful demonstration ever held in the United States.

The era of segregation and discrimination was horrific in many ways with society-wide and ongoing implications. This legacy affects society on many levels today, yet many are forging ahead and seeking to heal the present by interpreting and discussing the past. Throughout this history, we see that individuals from all races and backgrounds came together under the most trying of circumstances. Oral history is a powerful and effective tool for documenting the stories of such individuals.

Through oral history interviews, students not only document history, they make a direct connection to the history of civil rights in a way that is meaningful to them. By creating structured dialogue in their interviews, students can explore the concepts of memory, justice, truth, reconciliation, forgiveness, victim-hood, and reparation in society. Students gain a more authentic view, while raising their awareness as they consider how they might effect change in today’s social justice issues.

Organizations like the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute are providing refreshing and innovative approaches to teaching this important part of American history.

+++

A Summary of Apartheid’s History

South Africans share a painful past that includes many decades of racial discrimination. Yet, throughout this history are the stories of leaders and of ordinary people overcoming racial barriers to create a contemporary and culturally rich democracy. Their stories build meaning into history and teach us valuable strategies for the social justice issues of today, and for future generations.

Apartheid is defined as the social and political policy of racial segregation and discrimination enforced by a white minority government in South Africa from 1948 to 1994.[1] The word “apartheid” is from the Afrikaans language that was developed over the years by Dutch colonists, and means “apartness.” While apartheid policies extend back to the beginning of white government in South Africa in 1652, it became codified, or officially written into law, in 1948 when the Afrikaner Nationalists came to power after a long struggle against British colonists.

A benchmark law that empowered South Africa’s white rulers was the Population Registration Act of 1950, categorizing people into three racial groups: Bantu (blacks), white, or Coloured (mixed race). A fourth category, Asian (Indians and Pakistanis) was added later. More apartheid laws were created, reflecting an insidiously racist perspective on human kind. The Group Areas Act of 1950 and the Land Acts of 1954 and 1955 assigned these racial groups to different residential sections, to different job and business categories, and prevented nonwhites from entering restricted areas without a special permit.

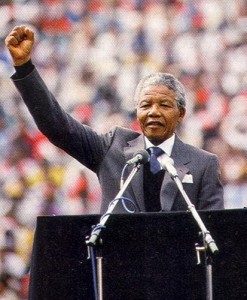

In the early 1990s, after a long struggle for equal and democratic rights, and under external pressure from the governments of the United States and Great Britain, the apartheid system was ended under the presidency of F.W. de Klerk. In 1994 the South African constitution was rewritten and the first democratic election held. Nelson Mandela, a prominent leader in the struggle against apartheid, was elected the first black president. Mandela was a political prisoner for 27 years prior to the election, and because of his inspirational impact he is called the Father of South Africa. Both Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their leadership in the transition from apartheid to democracy without a civil war.

In the early 1990s, after a long struggle for equal and democratic rights, and under external pressure from the governments of the United States and Great Britain, the apartheid system was ended under the presidency of F.W. de Klerk. In 1994 the South African constitution was rewritten and the first democratic election held. Nelson Mandela, a prominent leader in the struggle against apartheid, was elected the first black president. Mandela was a political prisoner for 27 years prior to the election, and because of his inspirational impact he is called the Father of South Africa. Both Mandela and de Klerk were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their leadership in the transition from apartheid to democracy without a civil war.

An important role was played by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), led by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, as the government turned its efforts toward healing and moving forward. The TRC heard thousands of testimonies from around the country in an effort to document and understand the effects of apartheid on all South Africans.

South Africa’s new democracy is founded in a national constitution considered to be one of the world’s most inclusive and progressive because in addition to protecting racial equality, it includes environmental rights, language rights, and access rights to health care, food and water. For details on the South African Constitution, go to